Here I will go a little bit ahead and ask the following: Why were exhibitions of book graphics so interesting in the Soviet time? I have very vivid memories. I first submitted my illustrations to such an exhibition in 1983. Imagine, there were exhibited such masters as Heorhii Yakutovych, Serhii Artiushenko, etc.—I can’t even remember them all now. I was one of the youngest participants at that exhibition. Exhibitions of book graphics gave artists the opportunity to paint on any topic. If artists painted on specific topics, they were confined to certain frameworks; they could not express themselves frankly and openly. Children’s books, however, provided a great scope for creativity. Artists could work on any topic. You can have the Cossacks, the Kyivan Rus, the fairy tales.

Moreover, there was practically no such thing as the underground art in Kyiv. In Moscow, everything was easier, and there were underground exhibitions since the 70s, with no objections from the authorities. When I went to see one such exhibition, there were long lines of people queuing. There were lots of foreigners. There was a demand. There were some intellectuals who supported such artists. In Kyiv, we had some individual cases, but the underground did not exist as a widespread phenomenon.

In addition, the generation of artists who worked before the Sixties was very small in number. Many of them did not return from the war, and some were repressed. So the generation that graduated from the art institutes in the 1950s was very talented. They began to work actively in children’s books illustration. I think illustration was in its prime at that time. I can even give you the time frame. In my personal opinion, the late fifties, sixties, seventies, and the early eighties were the rise of Ukrainian book graphics (although the printing was far from perfect). Later, it wasn’t as good. You can still find some good works now though.

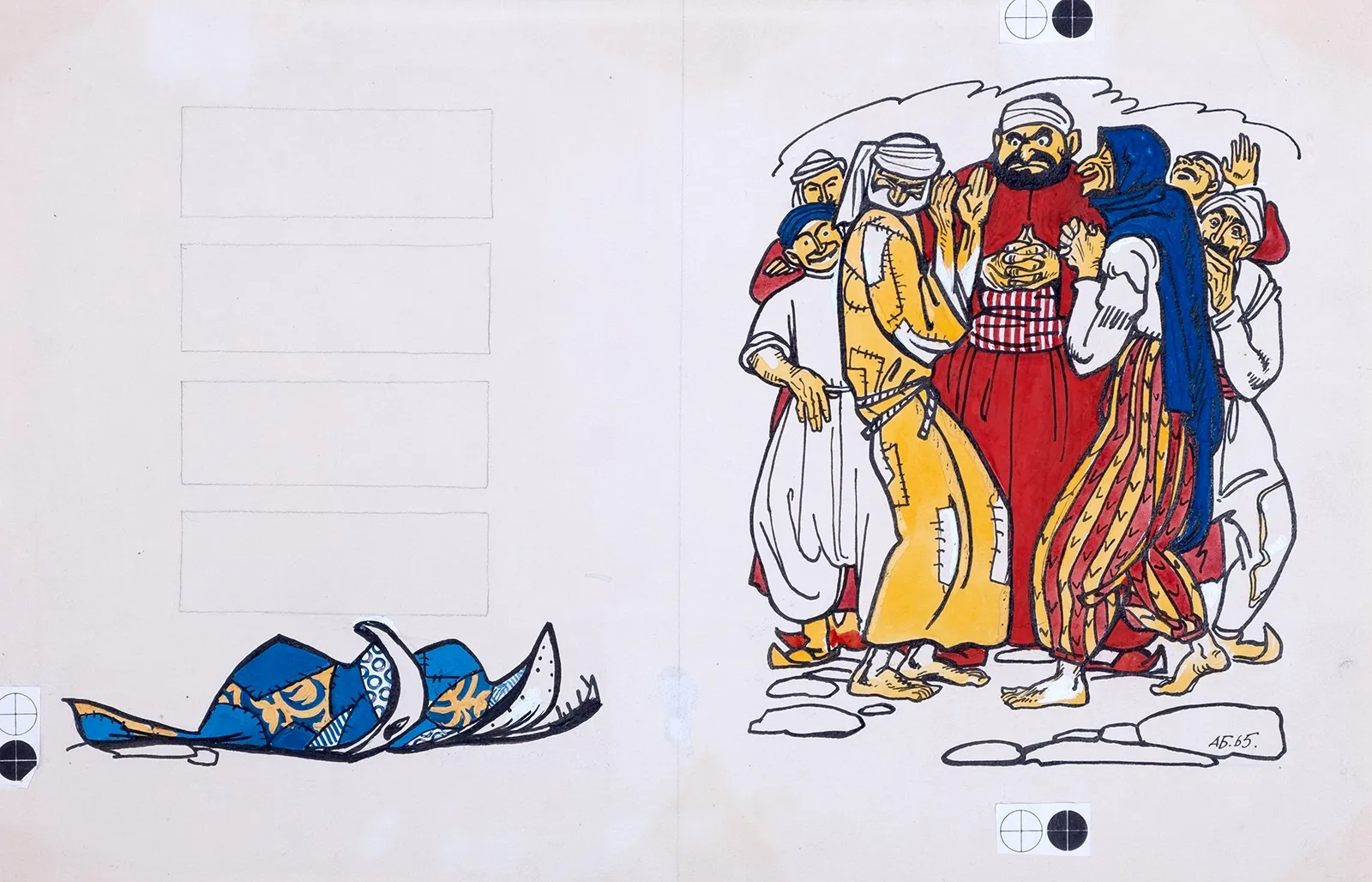

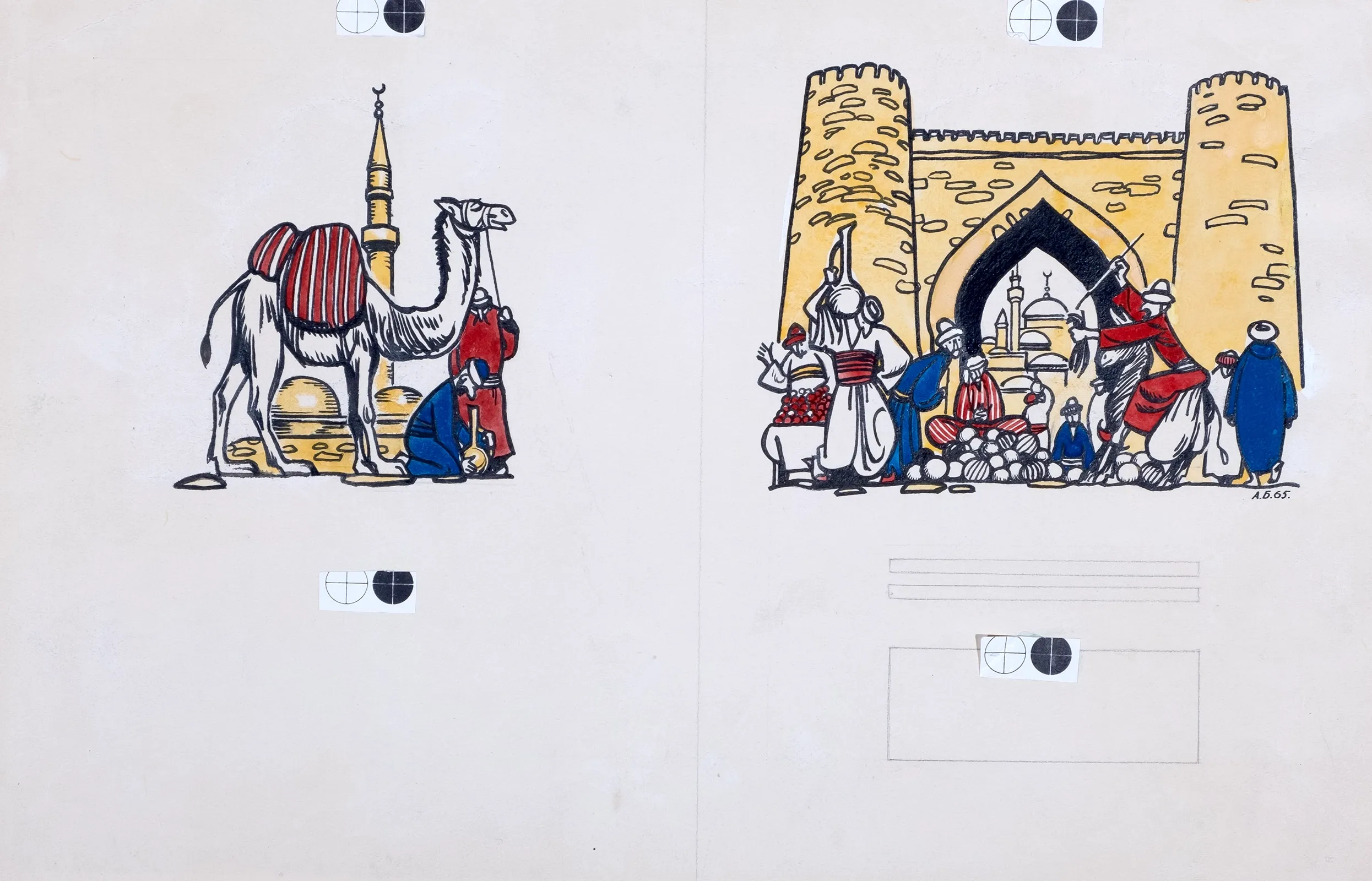

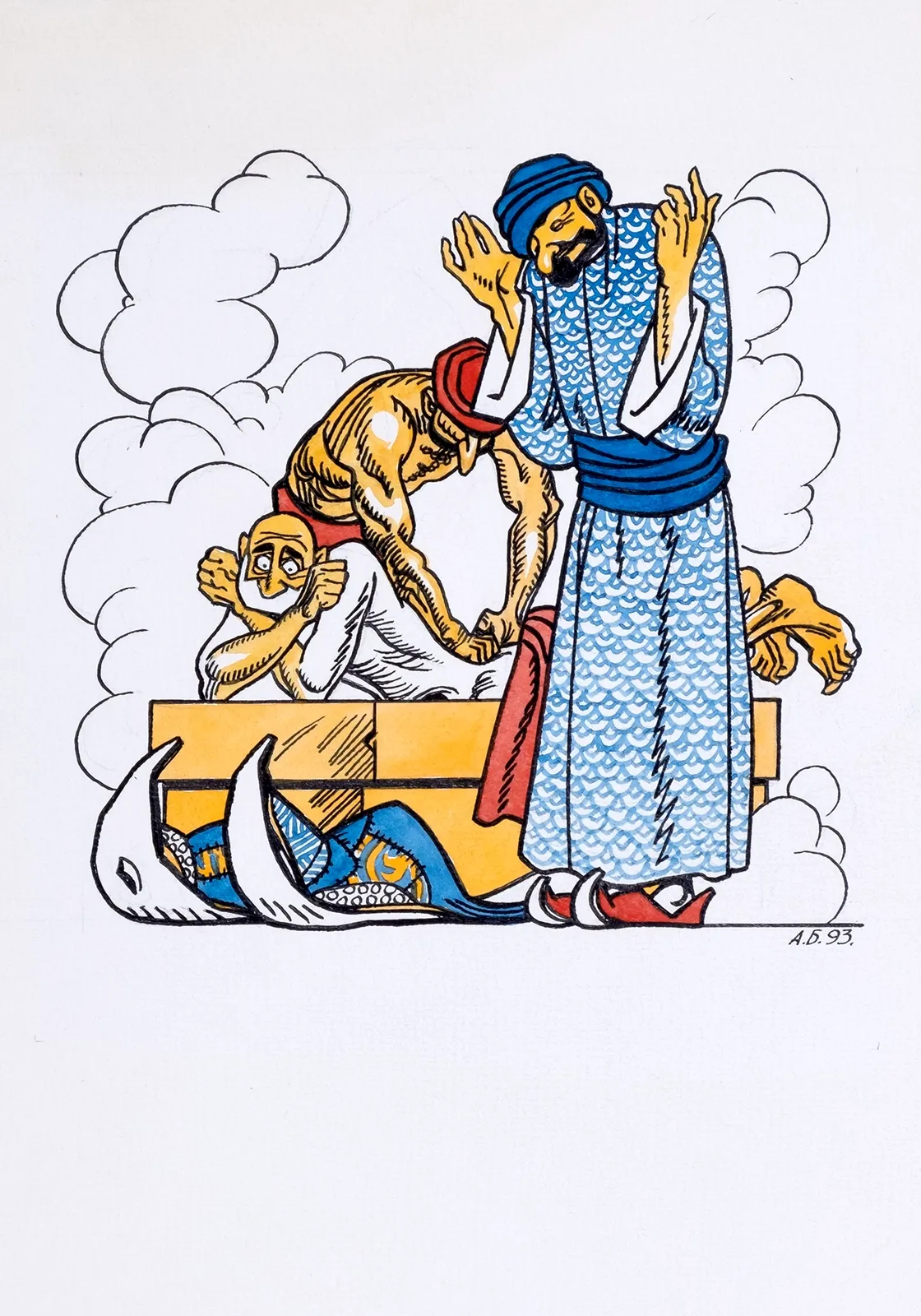

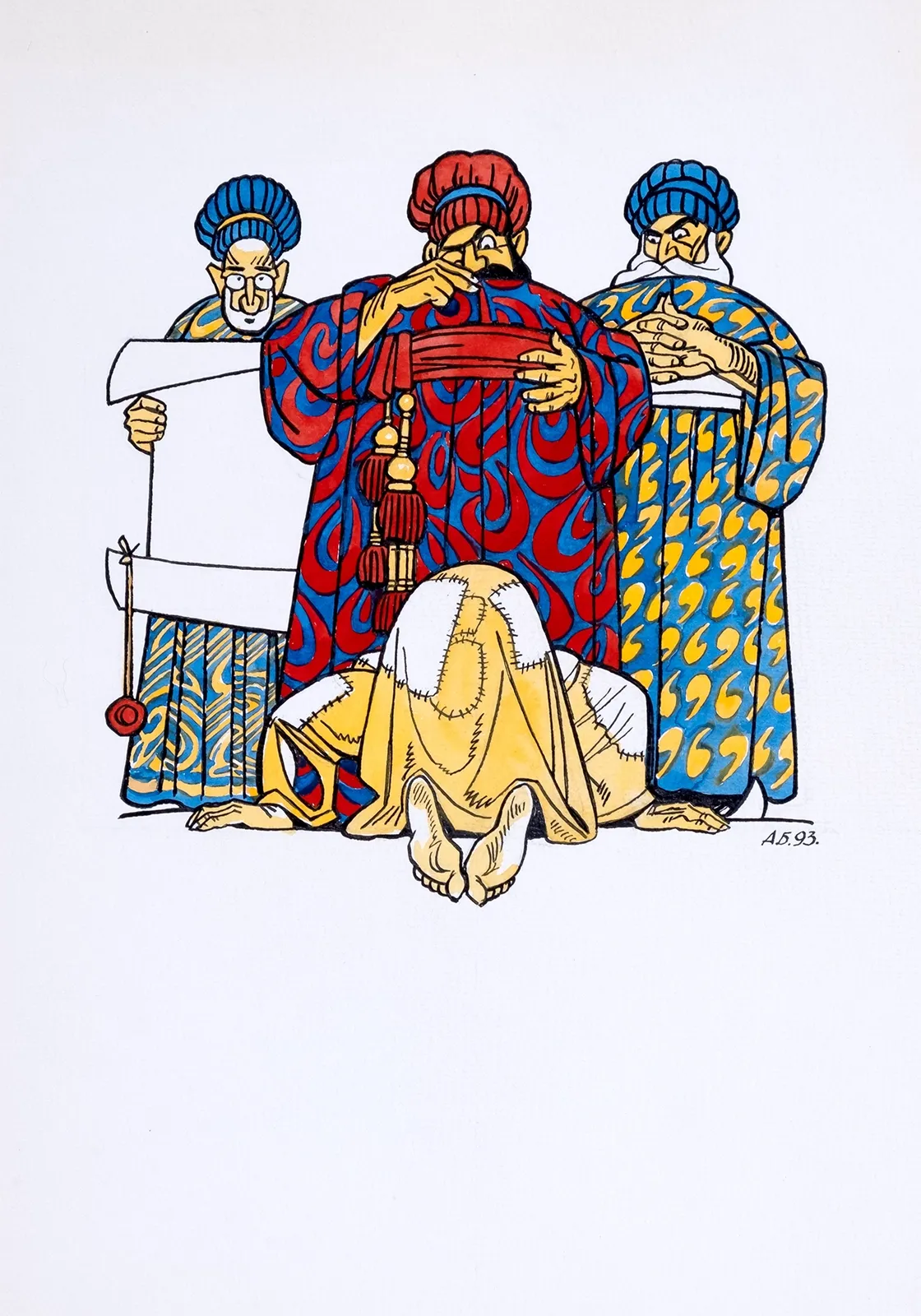

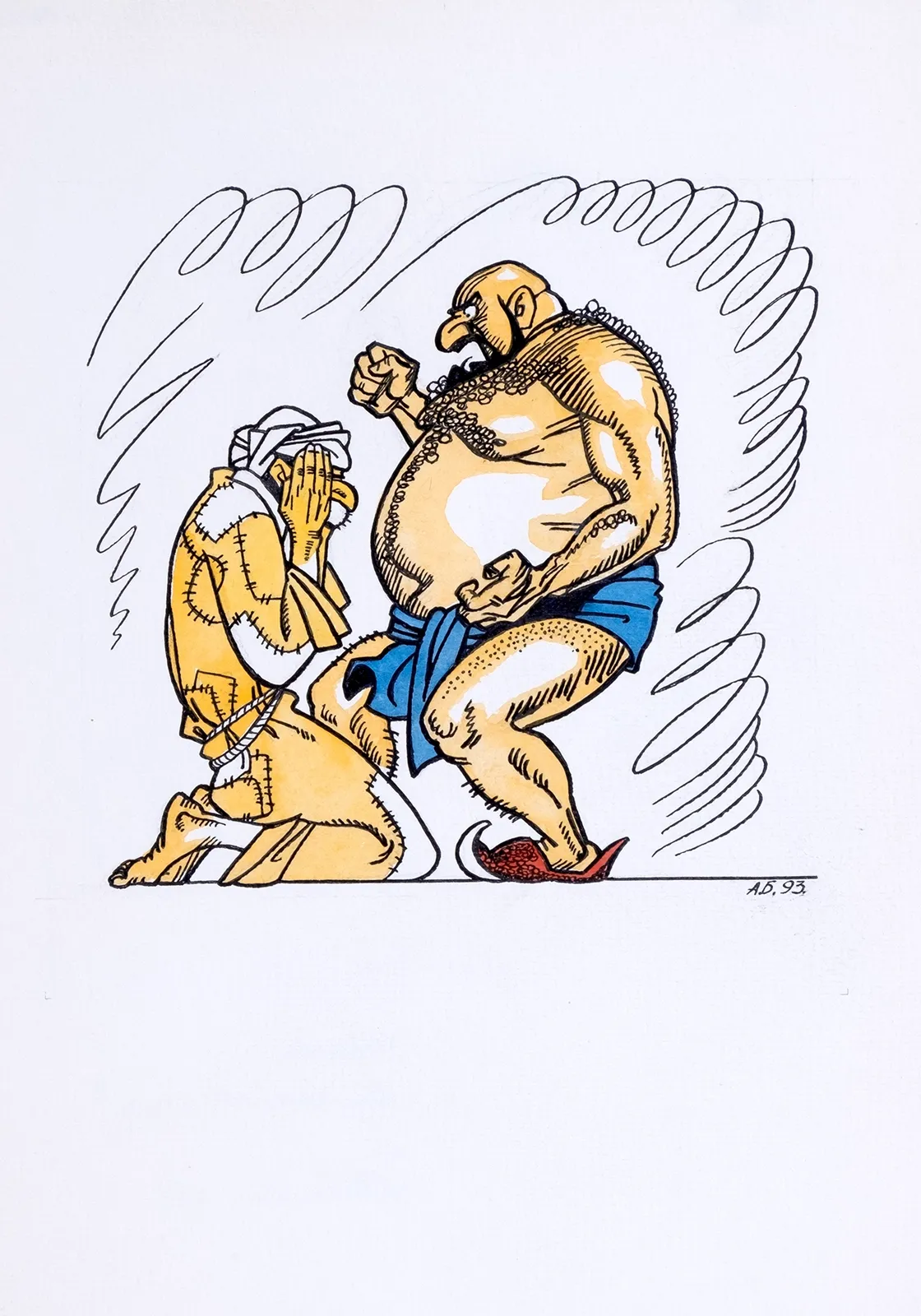

There were some artists who worked exclusively in children’s books illustration. What was unique about my father? His work was distributed somehow evenly: illustrations for adult books and illustrations for children’s books. His illustrations for adult books are better known: Kotliarevskyi’s Aeneid, Sholokhov’s The Quiet Don, Kvitka-Osnovianenko’s Pan Khaliavskyi, and Hašek’s The Fateful Adventures of the Good Soldier Švejk. His illustrations for children’s books, however, seem to be in the shadows. Meanwhile, my father did not make any distinction between them: he took both seriously, and there were no fundamental differences in his approach to adult books and children’s books. As for the subject matter (topics), my father worked in two directions: folklore (folk and literary fairy tales) and historical fiction.

I remember some of my father’s friends. Say, Heorhii Malakov. He worked a lot in children’s books illustration and was extremely popular. He also worked as an easel painter. Malakov made illustrations for Boccaccio’s Decameron, but unfortunately they were not published—for some reason. These illustrations now exist only as easel drawings.

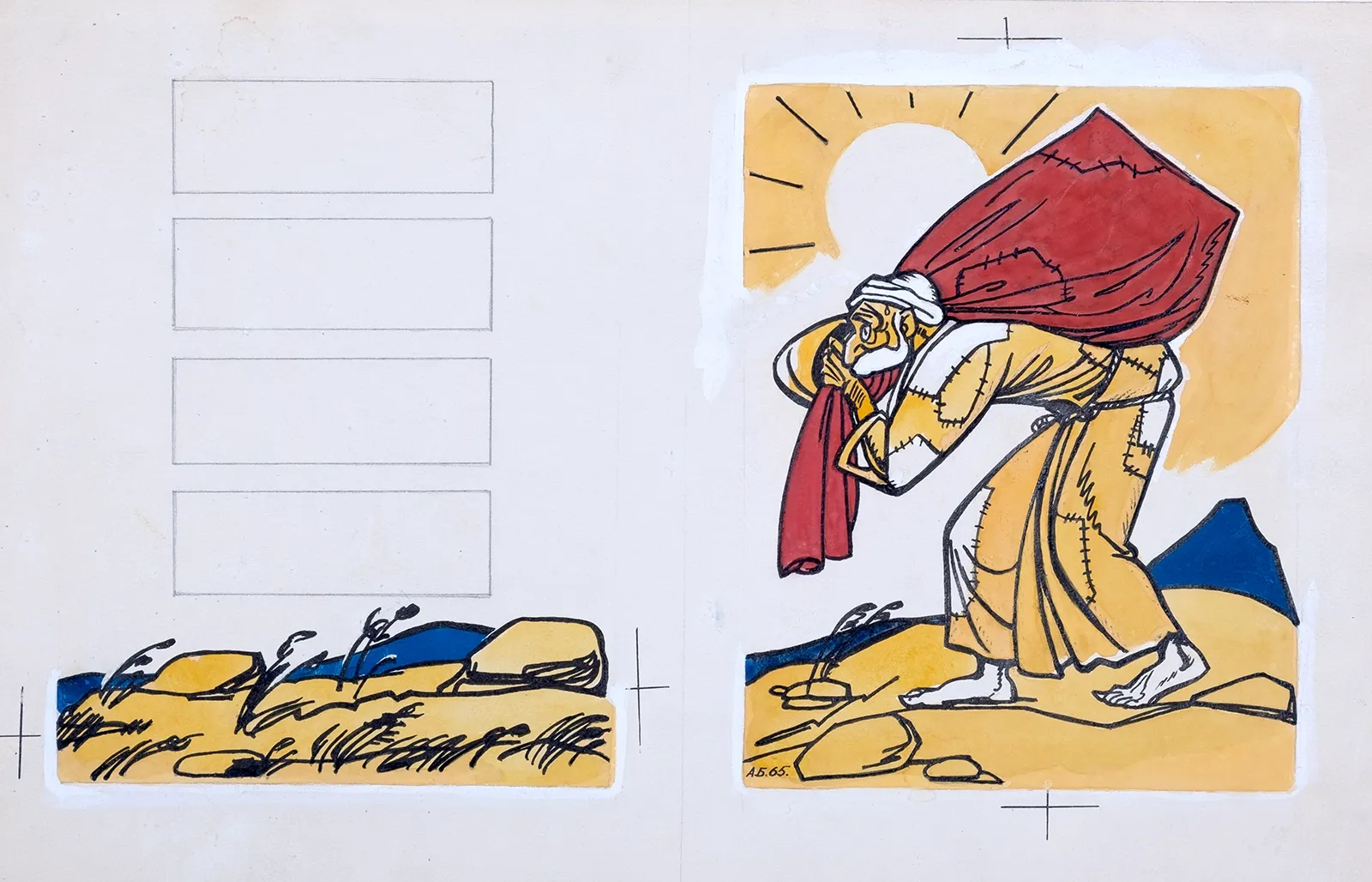

Heorhii Yakutovych also made a few interesting children’s books. And he was also engaged in easel graphics. Yakutovych is best known for his illustrations for the book Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors. He did a grand work for the Veselka publishing house: «Повість временних літ» (Primary Chronicle, or Tale of Bygone Years). In my opinion, this work is more adult in style because it is quite complicated, both in terms of composition and execution.